Harrison County: Ground Zero

Larry C. Timbs Jr.

Special to Publishers' Auxiliary

Apr 1, 2020

Because of the onslaught of the deadly coronavirus (COVID-19), we are living, as the president of the United States tells us every day, in “unprecedented times and nothing like this has ever happened in the history of our country.”

Schools are shutting down, local and national sporting events are being canceled, stores are closing or drastically changing the way they do business, workers are being laid off and fully one-third of the U.S. economy has slowed or come to a halt.

Not to mention that as this issue goes to press (March 29), more than 700,000 people worldwide are infected with the coronavirus and almost 32,000 people (including more than 2,300 in the U.S.) have died from the disease.

So what to do about the situation, for the benefit of your community, if you’re a local weekly newspaper editor in Cynthiana, Kentucky (population 5,600) about half way between Lexington and Cincinnati?

If you’re Becky Barnes, longtime editor of the 5,000 circulation Cynthiana Democrat, the stakes are even higher when you learn — at first through an unofficial grapevine — that Cynthiana, the county seat of 18,000 population Harrison County, Kentucky, just happens to be ground zero for the coronavirus in the Bluegrass State.

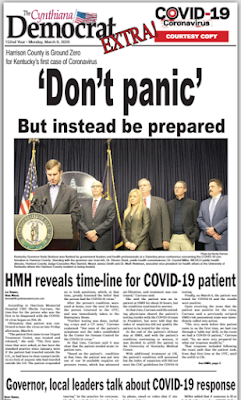

When Barnes tagged along on a Saturday with Harrison County’s judge executive and with Cynthiana’s mayor to a hastily called governor’s press conference in Frankfort (about an 80-minute ride from Cynthiana), her fear was confirmed.

Little old Cynthiana, a community she describes as “typical small-town America,” indeed had been stricken with the first case of COVID-19 in Kentucky, and so on the ride back from the press conference in Frankfort, Barnes’ brain began racing.

She had a huge story — maybe a once-in-a-lifetime story — to share with her readers, and she figured they needed as much useful, truthful information about COVID-19 as she could get to them.

The challenge, however, was that on that Saturday ride back from Frankfort, Barnes knew that the Cynthiana Democrat wouldn’t be printed until Wednesday (four days later) and wouldn’t be in the hands of readers till Thursday.

Barnes’ solution to get the story out earlier: print a four-page broadsheet special section on Sunday (one day after the press conference) and get it free into every home, mailbox and business in Harrison County.

Certainly, something called “the cost” — newsprint, labor and delivery — of putting out a special section must have run through her mind, but she didn’t let that stop her.

Instead, Barnes and another member of the Democrat’s three-person news department — Lee Kendall — worked their tails off on Saturday and Sunday (days they usually don’t come into the office) to create the copy and pictures for the special section and to paginate it.

Bottom line: the localized (for Harrison County) COVID-19 special section was ready to go to the Cynthiana Democrat’s in-house press by 2 p.m. Sunday, and it was coming off the press an hour later.

What they produced was an attractive newsy front page, featuring a picture from the governor’s press conference and a story by Kendall focusing on the local hospital with a timeline for the community’s first COVID-19 patient.

In addition, Barnes, who describes herself as a graduate of “the school of hard knocks of journalism,” wrote about the press conference, about some of the things happening (as a result of COVID-19) in the local schools and what some local leaders were doing to handle the virus-stricken community.

The special section also featured a column written by the school superintendent about how and why school would be closed and a column written by the local public health director geared specifically for Harrison County — focusing on how to deal with events and public gatherings.

MISSION ACCOMPLISHED

Shortly after all the quick writing, production and printing of 18,000 copies, an edition was delivered to every home and mailbox in Cynthiana and Harrison County — not to mention that the newspaper, owned by Landmark Community Newspapers, printed a bunch of extras to give to businesses, including pharmacies around the courthouse, city hall, Harrison Memorial Hospital and other places folks congregated. Copies of the special section also went to nearby communities — to residents who come to Harrison County to shop or for other reasons.

“It was just important that as many people as possible get the information,” Barnes said. “We tried to make sure that everybody got one,” whether it was placed in their mailbox or personally delivered to them. “If someone let us know they did not get one, somebody here in the office would either run it to them or take it to their address …

“And I think it helped calm some fears,” Barnes said. “It let people know what they needed to do and what our leaders were already doing for them.”

BUT BACK TO THAT MATTER OF COST

How the devil to pay for what could be called an emergency journalism rescue effort? Because if you’re like the typical small-town weekly newspaper, you don’t exactly have money to burn.

Barnes isn’t sure about the money aspect, but she thinks maybe the Cynthiana Democrat will get help on finances from local government.

Regardless, she says the little paper didn’t do it for the money.

“We didn’t do it so everyone else could pay for it,” Barnes said. “We did it because it was important for our community to know.”

It should also be noted that Barnes is a borderline high-tech community journalist. She has a little iPhone 6 that she regularly shoots video with at the health department (called WEBCO in Cynthiana), and when she found out that Harrison County had the first case of COVID-19, she posted live on the newspaper’s Facebook page, resulting in 90,000 people going to that page.

So what’s been the overall reaction from the community (which as of march 18 had six cases of covid-19)?

“It’s just been an overwhelming response,” said Barnes, editor of the Cynthiana Democrat for 30-plus years. “The community has embraced the newspaper and the information that we provided from our little special section and from that same week’s newspaper.

“… I think all this has just reaffirmed for me the importance of getting news to the people. When I got into journalism, I was, like most, very idealistic. I’m going, you know, to make a difference, and I think I did (here).

“This is something we all prepare for but we’re not ready for. It’s been interesting. And the community, when you call them and say, ‘This is what I’m doing,’ they’re like ‘Oh yeah, what can I do? What do you need to know?’ I couldn’t have asked for any more support from our community and our community leaders. It’s been great.”

Larry C. Timbs Jr. is a former community newspaper editor and retired journalism professor living in Surfside Beach, South Carolina.